The Brains Behind Watson

CSAIL professor helped computer win at Jeopardy!

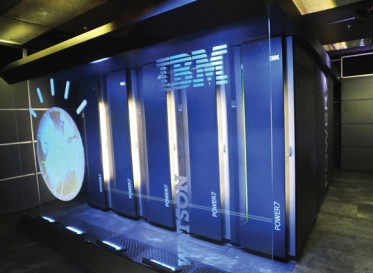

In February, the game show Jeopardy! pitted its two most successful contestants against an IBM computer system called Watson, which defeated them soundly. Several of the strategies that Watson used were based on research by Boris Katz, a principal research scientist in the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

In the early 1980s, Katz began developing a natural-language question-answering system called START, which went online in 1993. But automatic question answering ultimately gave way to search engines like Yahoo and Google, which provided less precise answers but were much easier to implement.

In 2003, however, the National Security Agency launched a program to develop a natural-language question-answering system, which brought together leading researchers in the field, including Katz and an IBM group.

“By the middle of this program, pretty much everything that is used in Watson was already invented,” Katz says. One design principle that Watson borrowed from START was Katz’s notion of ternary expressions. Katz illustrates the idea with a clause from Tom Sawyer: “Tom examined two large needles which were thrust into the lapels of his jacket.” START represents the semantic assertions of the clause as a series of three-term relationships, each consisting of a subject, a relation (such as a verb or preposition), and an object or property: Tom examined the needles, Tom has a jacket, the jacket has lapels, the needles are large, the needles are paired. Many natural-language-processing systems parse sentences into trees of grammatical relationships, similar to sentence diagrams. But the ternary expressions, Katz explains, are “much easier to understand, to store, and to match if you want to ask questions.”

The IBM researchers, Katz says, used several information retrieval techniques, including simple keyword searching as well as START’s parsing and analysis. But they executed them “an order of magnitude better than everyone else did,” he says. To Katz, the most important aspect of Watson’s design was its ability to evaluate the relative merits of the thousands of candidate answers provided by those techniques.

Though Watson won the contest, Katz says, its occasional blunders demonstrate that it is not capable of anything like human cognition. Given a question in the category “U.S. Cities,” for instance, Watson answered, “Toronto.” “It’s a great achievement,” says Katz, “but it’s not yet the holy grail.”